Enjoy this feast of activities for all seasons—activities that you and your family can enjoy without a guide.

WINTER

Make a Story Wreath

We put together these short videos in 2020 when we did a remote wreath making workshop. Short and sweet, they contain the information you will need to find beauty in the winter woods and fashion it into holiday cheer.

You will also need :

- Florist or wreath wire (available at hardware or craft stores)

- Pruning shears (recomended)

- Gloves

- Cookies and Cocoa!

December Night Skies

December brings the Geminids, the best meteor show of the year. The shower takes place from December 7 – 17. The best night to watch will be the night of December 13/14, with the peak occurring at 2 am. At that time, you might see as many as 120 multi-colored meteors per hour. With the moon nearly new, the skies will be dark, making for a great show. The meteors will radiate from the constellation Gemini, but may be visible across the sky.

Catching Snowflakes

H.D. Thoreau, 1856

Snowflakes are crystals that form when water vapor freezes, becoming a solid without passing through the liquid phase. The molecular structure of water is such that all snowflakes grow as hexagonal prisms. With the right conditions, these form as tiny six-sided plates, and as they begin to tumble to earth, more water vapor joins the crystal, adhering most readily to the corners of the hexagon and growing into points and elaborate branching patterns. The best conditions for the formation of big, beautiful snowflakes are temperatures in the single digits with some moisture in the air. On such cold days you are mostly likely to see the classic snowflakes called stellar dendrites (stars with tree-like branching). As Thoreau noted, such flakes can be observed as they fall upon your coats or mittens, but it is easier to admire individual flakes, and preserve them a little longer, if you have a snowflake catcher. Snowflake catchers are easy to make. The essential component is a piece of black (or dark colored) felt. This can be used on its own or made more rigid by attaching it to a cardboard frame, plastic lid, or a plastic plate. Store the catcher in your freezer (or put it in long enough to chill the surface). Do you have a magnifying glass? These two items will make your snowflake safari even more thrilling.

Winter Bird Watching

Here are a few ideas for learning more about birds during the ongoing distancing from human friends and neighbors:

Yearning for a little contact? With patience, you can get some of your feeder birds to perch on you. Chickadees, nuthatches, and titmice are all curious and adventurous. Chances are good they already connect you with the arrival of food, especially if you go out each morning at around the same time to restock empty feeders. If the birds are already gathering, simply hold a handful of favorite seeds or nuts in it near the empty feeder and close to a perch. It may take a few days of swooping in and then shying away before the first bird gets up its nerve to take a seed from your hand, but once one birds does it, others will soon follow. Always move slowly and talk softly. If you have more time than patience, you can make a dummy and position it in a chair in your feeding area. Give it a distinctive hat and coat, and fill its lap with bird seed. Once the birds are accustomed to feeding there, just swap yourself for the dummy, donning the hat and coat, and see what happens. Again, this works best when the nearby feeders are empty.

Spring

Vernal Pool Party

Things are hopping in vernal pools right now. Is there a vernal pool near you that you can visit? If you’re not sure, visit our Salamander Crossing Site map. Chances are good that if there’s a crossing site, there will be a vernal pool nearby. If you’re out in the woods and hear a flock of ducks quacking, the chances are good that you’re near a vernal pool. These will be wood frogs:

Vernal pools are small, usually temporary, bodies of water that are found in the woods and are isolated from other water bodies. These pools provide critical habitat for spotted salamanders, wood frogs, and other neat critters. From now through June (and until they dry up) they will be teeming with life. They are fascinating places to visit.

Learn about the amphibians that breed there—spotted salamanders, wood frogs, and Jefferson salamanders at the Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas Project.

This pdf will help you identify the frog and salamander eggs: Egg Mass id web

Vernal pools are small, usually temporary, bodies of water that are found in the woods and are isolated from other water bodies. These pools provide critical habitat for spotted salamanders, wood frogs, and other neat critters. From now through June (and until they dry up) they will be teeming with life. They are fascinating places to visit.

Learn about the amphibians that breed there—spotted salamanders, wood frogs, and Jefferson salamanders at the Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas Project.

This pdf will help you identify the frog and salamander eggs: Egg Mass id web

Timberdoodling!

When: Any evening after sunset (between 7:30 and 8:30) through May

Where: Fields or meadows, especially with damp, brushy spots

This is woodcock courtship season—a rite of spring that can be witnessed within walking distance for many of us. Do you live near a pasture or meadow, especially a damp one? Head there at dusk to enjoy the courtship flight of the timberdoodle.

In this Second Nature article, you will find more details and a description.

This View from Heifer Hill column describes the puzzle of the woodcock’s silly walk.

Here’s great video footage of the woodcock courtship display

A woodcock family doing the rock/bob

A woodcock feeding while doing the rock/bob

Sunset Ledges

When: Between 6 and 7 pm (or your local sunset time) before leaf-out

Where: Steep, west-facing hillsides, especially ones with rock outcroppings

The sunset colors in the woods in April are glorious. We recommend finding the nearest steep hillside where you can see the setting sun, but instead of watching the sun, watch the way it paints the forest. Moss- and lichen-covered rocks are especially beautiful. Find a good spot to sit and enjoy the show. Evening bird songs might include geese heading north, robins chirping their good-night songs, and perhaps the song of a hermit thrush.

If you choose the right spot, you might even meet a porcupine.

Read about Patti’s evening with Big East for inspiration: Facing West with Big East—April 2020

Bittern Quest

When: Sunset or dawn in May Unchanged:

When: Sunset or dawn in May

Where: Marshlands

The American bittern is one of the most elusive and peculiar birds in our region. These members of the heron clan disappear in tall grasses, sedges, and cattails, especially when they deploy their invisibility pose—long bill pointed heavenward, body swaying so the vertically streaked plumage becomes grass in the wind. You probably won’t see one, but if you’re lucky you might hear one. Click on the videos below to hear the strange sound they make and to see how they do it.

Bitterns are not common, but if you head to good bittern habitat at dawn or dusk, you will be bound to see many of the other species of birds that live in marshes. Keep an eye out for muskrats too. These guys look like miniature beavers, but their tails are not flat. If they are swimming, their tails create S-shaped ripples behind them.

If we were gathering this spring, we’d invite you to join us in Somerset to bike to the marshes on Castle Brook Road. If travel restrictions loosen up, you might plan to head there on your own. Castle Brook Road is an unmaintained Forest Service road that heads west off of the access road to Somerset Reservoir. The marshes are about a mile in. The timing is tricky. You really don’t want to visit these marshes during mosquito season. The best window is likely to be in early May.

To find potential bittern listening locations nearer you, explore this e-Bird map showing places where bitterns have been reported.

This short video captures some interesting bittern behaviors.

This very short clip shows a bittern thunder pumping.

Peepers, Live!

When: Dusk into darkness through early June

If you’re craving a choral concert, spring peepers oblige. Pack a picnic, grab your sweetheart, and follow your ears to find the show. Spring peepers are very shy performers and will likely shut up if they detect your presence. If you manage to be quiet and still for more than a few minutes, the show will resume. Listen for the May accompanists: American toad, pickerel frog, and gray tree frog.

Peeper challenge: Try to spot one. It’s much trickier than you think! Send photos to

Bring ear protection. Seriously.

Here’s what the other frogs sound like:

Listen to the “snore” of a pickerel frog .

Here is the prodigious trill of an American toad.

Gray tree frogs call on warm nights. You really want to see one of these!

Spring Greens

When: May

Where: Your backyard?

Garlic mustard displaces native plants. It often grows in colonies and can thrive in shade or full sun.It releases chemicals from its roots that suppress other plant growth. When you find a patch, be sure to take far more than you need.

Japanese knotweed has taken over stream and river shores. The newly emerging shoots are tangy and reminiscent of rhubarb, in fact some people substitute knotweed for rhubarb in recipes. Harvest shoots when they are less than a foot tall, before they start to become woody. Later in the season, the young growing tips can be eaten.

The Good Old Summertime

Thrush Light

“The thrush alone declares the immortal wealth and vigor that is in the forest. Here is a bird in whose strain the story is told…Whenever a man hears it he is young, and Nature is in her spring; whenever he hears it, it is a new world and a free country, and the gates of heaven are not shut against him.”—Henry David Thoreau

As the bustle of the day fades, some of the loveliest bird songs on the planet fill the darkening woods. The richness of thrush song is a result of their unusual vocal chords—they are capable of singing two notes at once. The reverberations create chords that are music to our ears.

The wood thrush, hermit thrush, and veery are the three you are most likely to hear in our region.

The veery’s call is easy to recognize, a rich series of descending notes.

The hermit thrush and wood thrush have complex songs that can be tricky to distinguish. They sing two- to three-second musical phrases with numerous variations.

The hermit thrush, Vermont’s State Bird, begins each musical phrase with a sweet, whistled note. The next phrase begins on a different note.

The wood thrush’s song often starts with a few soft, quick notes, and often incorporates a version of their distinctive ee-o-lay notes in the middle.

The hermit thrush has a rusty tail and lighter speckles than the wood thrush.

Did you know that robins are thrushes? You will also hear their repetitive sing-song at dusk, as well as their “good night” tu-tut-tuts.

Head out for a stroll at twilight and enjoy the concert. Depending on your woods, you might also here the haunting, clear song of a white-throated sparrow— “Poor Sam Peabody, Peabody, Peabody” or the virtuosic, long, rapid, squeaky-hinge song of a winter wren.

Singing insects

All summer they’ve been growing, and now they are ready to perform. Around thirty different cricket and katydid species join in chorus in our region. Their concert peaks around dusk on warm evenings. Go out and listen any time and see if you can begin to pick out some of the distinctive performers. You can hear recordings of the different calls and see photos of the singers at Lang Elliot’s wonderful website Songs of Insects.

Here are a few to listen for:

On warm evenings, these loud grating calls can be heard from the trees. The name invites you to imagine the accusation “KA-TY-DID!” reapeatedly. Sometimes you can hear “NO-SHE-DID-NT.”

Deleted: Snowy tree crickets sound a lot like fall field crickets, the ones that make the chirping sound we all associate with crickets. If you hear that sound coming from a bush instead of the ground, you are hearing the rich chirps of a snow tree cricket. You can use these chirps to tell the temperature. Count the chirps in 13 seconds and then add 40 to get a good estimate of the degrees Fahrenheit.

In meadows of asters and goldenrods, keep an ear out for this counting katydid! He begins each counting series with two or three “eenh” calls. This is followed by a pause of a few seconds and then a repeat, with another note added. The katydid continues until he reaches seven to nine calls and then starts again.

Find out how these insects make their songs, and learn to identify the songs of the ever-singing ground crickets here.

Monarch Watching

It has been a pretty good summer for Monarch watching. Monarchs have been in Vermont since early July and have been laying eggs and increasing in number ever since. The butterflies you see in September are likely to be the ones who will attempt the long flight to Mexico. Late summer is a good time to find caterpillars on milkweed. You are likely to find a lot more caterpillars on young milkweed plants, those that were mowed earlier in the summer. To spot the caterpillars, look for leaves that have been nibbled and for look for piles of “frass,” caterpillar poop, on the leaves below. Newly hatched caterpillars are TINY, less than a quarter inch long! They do not have stripes but are pale-colored and translucent and have short bristles. They begin eating and hardly take a break for the next two weeks. During that time they will outgrow and shed their skin four times. The period between each shedding is a developmental stage called an instar. Here is a graphic from Monarch Joint Partnership that illustrates the different instars. Can you find caterpillars in each stage?

You aren’t as likely to find a chrysalis since the caterpillars often move to a different plant to complete their metamorphosis. Monarch caterpillars are easy to care for and bringing them indoors may protect them from certain parasites. Here are some instructions for caring for caterpillars and watching their remarkable transformation.

Your monarch observations can contribute to the growing citizen science databases that may help save the imperiled migrating monarchs. Here are two projects that would love your participation:

Journey North engages citizen scientists from across North America in tracking migration and seasonal change to foster scientific understanding, environmental awareness and the land ethic. Volunteers submit observations of first monarchs in the spring, roosts in the fall as well as first emergence and presence of milkweed. Sign up for weekly news updates and watch real-time interactive maps.

Autumn

Eyeshine Safari

With darkness coming earlier, and before the onset of the deep freeze, get out with a light and look for eyeshine.

Purple and Gold

Asters and goldenrods are now in bloom and the meadows where they flourish are busy with pollinators. There are about 20 species of each that you can find in our region if you look hard enough. There are several common species that are abundant and distinctive. Most of these species grow in proliferation, so feel free to bring a bouquet indoors to admire. If you suffer from late summer hayfever, these flowers are not to blame. They are insect pollinated. Their pollen is too heavy to become air-borne.

Here are a few common species to look out for:

Goldenrod

Asters

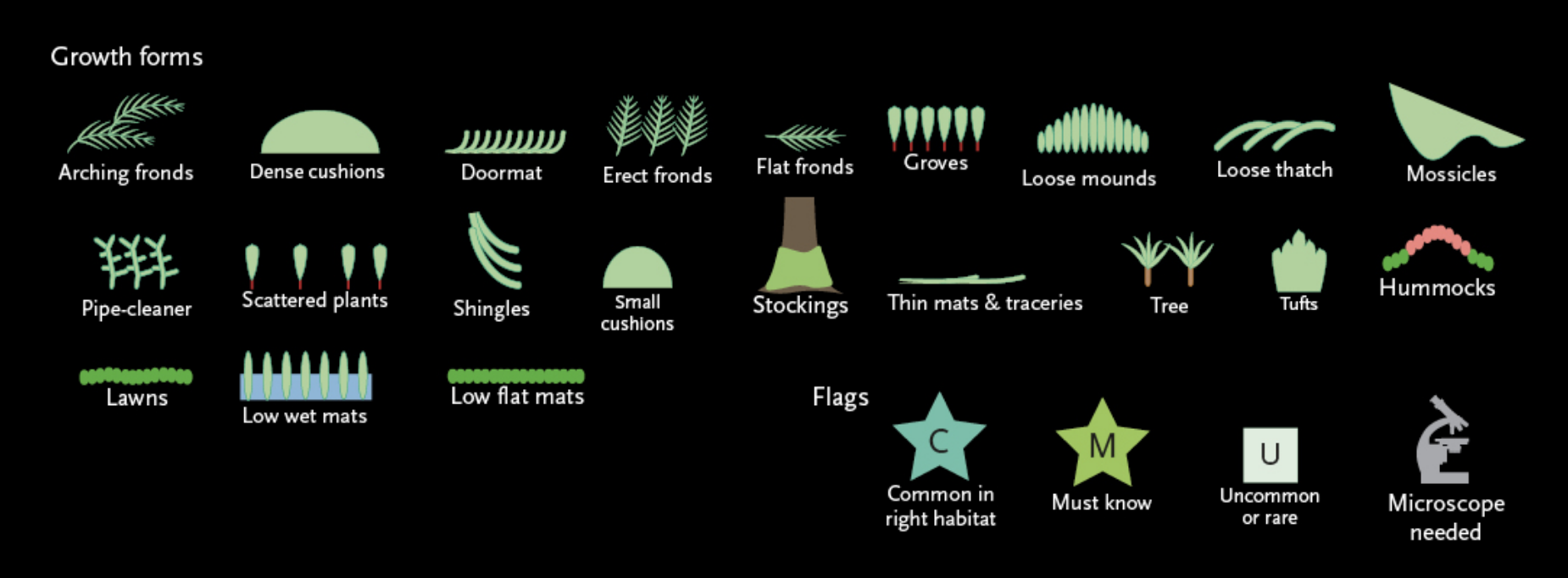

From Mosses of the Northern Forest – A Digital Atlas by JC Jenkins & S Williams

Celebrating Mosses

Stick Season is a wonderful time of year to develop your appreciation of the lovely, lowly mosses. Allow the Mosses of the Northern Forest: a Digital Atlas by Jerry Jenkins and Sue Williams to be your guide. Produced by the Northern Forest Atlas, this resource will lead you as far along the mossy path as you would like to go. The Moss Atlas blends simple, clear graphics and user-friendly terminology with high-resolution close-up photographs and the technical vocabulary needed for those stalking an ID.

Our favorite part are the Moss Maps. They focus on the common mosses you will find on, say, a boulder in a dry forest or on a wet ledge. The maps show where on each feature you are mostly likely to find each moss. This moss atlas is a free download (though it’s a BIG file). You will find it, along with print versions and excellent moss lessons at the Northern Forest Atlas website.

November Night Skies

With darkness arriving early now, and temperatures warmer than they will be in soon, November is a great month to explore the heavens.

With darkness arriving early now, and temperatures warmer than they will be in soon, November is a great month to explore the heavens.

November brings two meteor showers

The Taurids radiate from Taurus throughout the month, peaking on November 12. You can expect to see about 10 meteors an hour.

The Leonids peak on November 17, with 20 meteors per hour(ish). Most will radiate from, you guessed it, Leo.

Need help finding these constellations? There are some great apps available to help. Just point your device at the sky and the celestial objects and the apps will identify what you are looking at. Two widely recommended apps are Skyview and SkySafari.